As a shape note singer interested in its history, I’ve always found beauty and power in this unique American tradition. To see this 19th-century, Southern form of spiritual folk music continually finding new life in the 21st century, especially outside the US, is deeply moving. Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s new exhibit “The Call” at the Serpentine in London does just that, using Sacred Harp as a springboard for a thought-provoking exploration of artificial intelligence and its role in artmaking.

What particularly excites me about “The Call” is the artists’ decision to use actual Sacred Harp singing as the foundation for their AI model. By recording 15 professional and community choirs from around the UK singing hymns, exercises, and improvisations based on the Sacred Harp tradition, Herndon and Dryhurst created a rich and unique dataset. This data was then used to train AI models to compose new pieces in a similar style, effectively creating a “new polyphonic language”.

While I don’t know how many people who are regular shape note singers participated, it’s apparent from images of the show that the four shape note tradition is used. While the tunes used originate (in some form) from The Sacred Harp, “a mix of professional and community choirs” were contacted to participate. Holly states in one interview “I wrote into the songbook [the idea of] ‘please take these hymns. and interpret it to the aesthetic of your group’”.

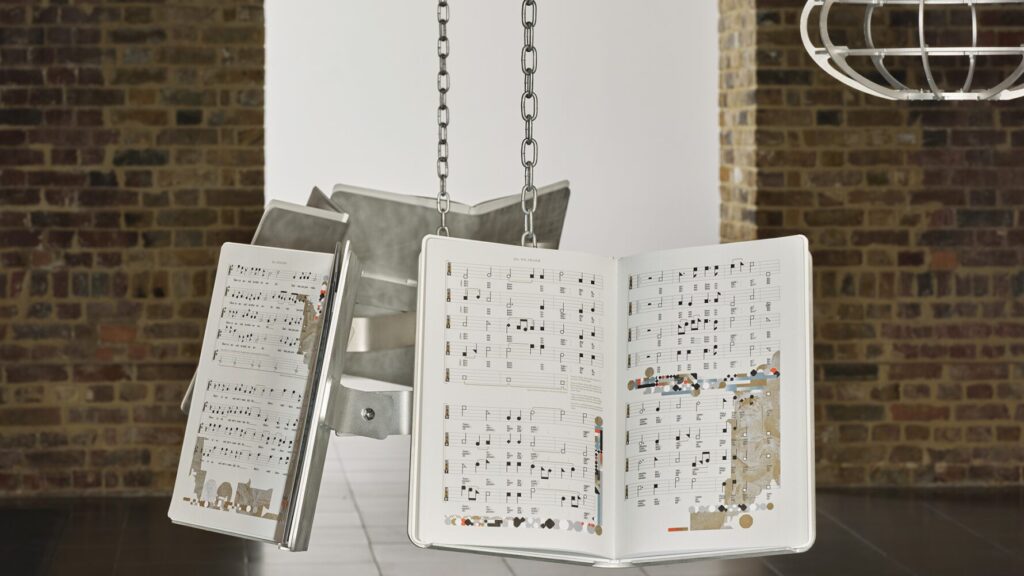

About the unique songbook, the artist elaborates: “We worked with a team (that) research(es) AI music notation—and we wrote a program based on a subset of the Sacred Harp canon. It can write infinite hymns. The songbook could be a thousand hymns, it could be two thousand.” While that might seem astounding to a casual reader, Sacred Harp singers know that just holding The Sacred Harp and The Shenandoah Harmony means they have over a thousand first rate tunes already at hand–no team of computer researchers needed!

The exhibit itself is a multi-sensory experience, with installations designed to evoke the feeling of being in the center of the hollow square. Visitors can listen to compositions generated by the AI, interact with the models through their own voice, and even explore the process of training data through visual elements like a chandelier representing the microphone rig used in recording sessions.

What I find particularly interesting is the artists’ focus on the collective and collaborative nature of both Sacred Harp and AI. Just as Sacred Harp singing involves a group of individuals coming together to create a unified sound, “The Call” explores the potential of AI as a “coordination technology” to facilitate collective art-making. The exhibit also addresses important questions about the ethics of AI and data ownership, with Herndon and Dryhurst working to create a data trust that gives the participating choirs control over how their recordings are used.

This aspect of “The Call” is particularly relevant to the history and spirit of Sacred Harp singing. Sacred Harp is all about community, with singers gathering in a square, facing each other and creating music together. There’s no audience, no performer hierarchy—just a shared experience of creating harmony. Herndon and Dryhurst have attempted to honor this in their exhibit, recognizing that both Sacred Harp and AI, when used thoughtfully and ethically, can be powerful tools for human connection and creative expression.

The UK and Ireland seem to have a particularly active community of Sacred Harp singers, and I’ve seen videos from Ireland All Day singings shared very often as some of the most compelling examples of the tradition. Writing about Sacred Harp and museums immediately evokes in my mind some of the near-cinematic videos by Manchester Sacred Harp of their monthly singings at an Art Gallery. The sound is just at home there as a clapboard Primitive Baptist Church in Alabama, or an 1840s stone Quaker meeting house in Maidencreek, PA.

The choice to feature Sacred Harp in a prominent London gallery is a testament to the enduring power of this musical tradition. It’s a powerful reminder that even a seemingly niche, very old, and regional art form can have a global impact and inspire creative exploration in unexpected ways. “The Call” is more than just an art exhibition—it’s a conversation starter, prompting us to think about the possibilities and challenges of AI, and the role of collective creation in the 21st century. It’s also an inspiring sign that this beloved tradition continues to resonate with artists and audiences across the globe.

Love this piece. We (Manchester Sacred Harp) are so fortunate to be hosted at The Whitworth Gallery each month – it’s wonderful to be accessible to people coming across Shape Note singing for the first time. We’ve also sung in Manchester Art Gallery, The Museum of Science & Industry, and the Royal Exchange Theatre. And, we’re wildly excited to be involved next month, at Aviva Studios (an amazing new Manchester arts venue), in a performance project with Laurie Anderson, ‘Ark: United States V’. 67 singers from across the UK, and beyond, over 10 shows.